|

|

Projects /

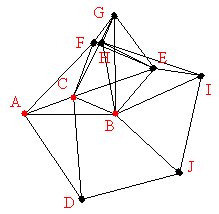

Sensor NetworksImprovements in sensing technology and wireless communications have greatly enhanced our ability to view and understand the world we live in. Collaborative networks of sensors can be deployed for relatively little cost, gathering and reporting real-time data about their locale. I am interested in the estimation and information processing problems which arise in sensor networks.  An example graph Sensor localization and message-passing algorithmsAn important first step in many sensor deployments is to localize the sensors, i.e., obtain estimates of each sensors' position and/or orientation. Almost equally important is to gauge the amount of uncertainty remaining in our estimates -- are our estimates sufficiently accurate, and if not, where do they need improvement? Self-localization methods, which exploit local measurements of relative position (such as received signal strength or time delay between sensors), are desirable to minimize cost and effort.

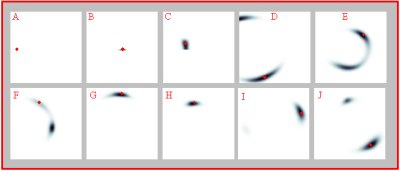

Beliefs after first iteration We formulate the localization problem as an inference problem on a graphical model, allowing us to apply generic inference algorithms from machine learning to estimate sensor position. In particular, we apply nonparametric belief propagation (NBP), a variant of the popular belief propagation algorithm. This provides a distributed estimation process in which each sensor sends local information to its neighbors, successively refining its position estimate. The resulting, distribution-like belief functions also provide estimates of the uncertainty in position for each sensor.

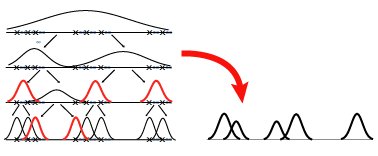

Communications cost for density estimates KD-Tree for density approximation In the localization problem, and more generally in object tracking tasks for sensor networks, sensors maintain a belief or posterior distribution about the objects' state (position, velocity, etc.), and must communicate these functions to exchange information. A typical example is "leader-based" tracking: a particular sensor is nominated as the "leader node" and tracks the object until it leaves that sensors' vicinity. At this point, the sensor "hands off" its leadership position to a closer sensor, sending its current estimate of the state to the new leader. How expensive is this hand-off process? For particle-based filters, it would seem to grow linearly with the number of samples. However, these samples comprise a density estimate, and it is reasonable to think that the asymptotic cost should scale with the complexity of the density, and perhaps with the fidelity to which it is represented. We examine this problem in some detail, and propose algorithms for simultaneously approximating particle-based density estimates and representing those approximations efficiently for communication. |